Analysis and history of 真

An alternative form of 真 is preserved in the character 眞, which features “fallen person” 匕 on top instead of 十. There is no consensus on the development of the character 真.¹ Similarly, there is no agreement on which oracle bone characters served as the predecessors of the later forms.²

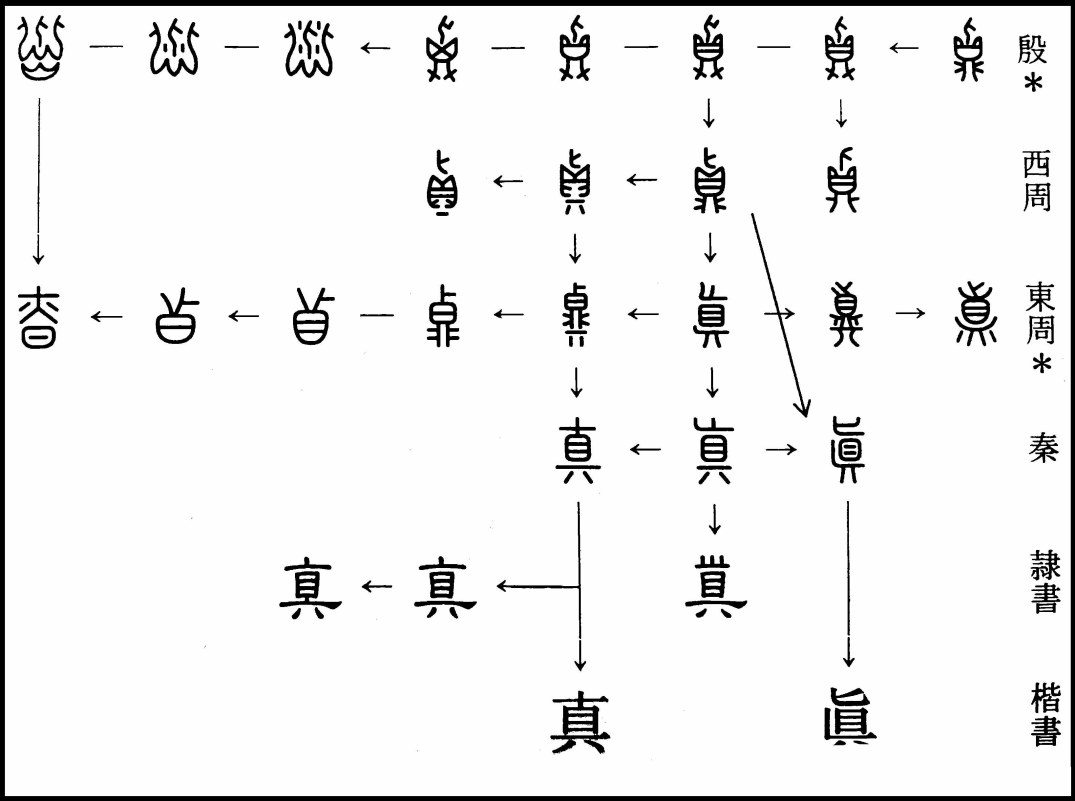

Ochiai identifies more than eight distinct oracle bone forms. Based on his analysis of these graphs, he interprets 真 as representing a large three-legged kettle with a person inside or above.³ One variant also includes droplets of water inside the kettle, while another shows fire beneath it (see the top row of the chart below). From this, Ochiai concludes that 真 is a semantic compound that represents the act of boiling a person alive.⁴

Regarding its earliest use, in oracle bone inscriptions the forms Ochiai associates with 真 appear as the name of a ritual. He therefore proposes that the original meaning may have referred to a ritual involving boiling a person alive.⁵ As for its later meanings, it is likely that the character was borrowed for its phonetic value.⁶

Identifying the oracle bone characters is crucial for analyzing the development of 真. In later forms, some variants feature a shape resembling “cowrie shell” 貝 beneath “fallen person” 匕, while others display a far more complex structure below the 目 component than 貝 does. If one accepts that the oracle bone forms depict a “three-legged kettle” like 鼎, then the more complex lower parts seen in most later variants can be understood as representing the legs of the kettle.

However, Chi concludes from his research that at some stage there was a mix up between 貝 and 鼎 as the core element of 真 and that the two were used interchangeably.⁷

As stated above, Ochiai analyzes 真 as a semantic compound. However, Chi and other scholars argue that 真 is a phonogram. In this view, the top part of 真 resembles the early form of 殄 (which looks like 𠂈) and serves as the phonetic component. Additionally, Chi references an analysis that suggests the bottom part of the character, which resembles 丌, is a corruption of 丁. In this interpretation, 丁 was added later as a second phonetic element.⁸ Other scholars consider 丌 a semantic element.⁹ It seems likely that, as with many other graphs, at some point the scribes did no longer understand what 真 represented, and as a result of that modified its shape in different ways that made sense to them, possibly swapping out elements or corrupting them beyond recognition.

Notes

References

- Chi 說文新證, 季旭昇 Chi Hsu-Sheng. 台北: 藝文印書館印行, [2004] 2014. (年9月二版).

- MFCCD 漢語多功能字庫 <https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/>

- Seeley et al. The complete guide to Japanese Kanji: Remembering and understanding the 2,136 standard characters, Christopher Seeley and Kenneth G. Henshall with Jiageng Fan. Tuttle. (printed in Singapore), 2016.

- Ochiai (2022) 漢字字形史字典【教育漢字対応版】 (Dictionary of the historical evolution of kanji forms: Edition covering all Elementary school characters), 落合淳思 Ochiai Atsushi. 東方書店 Tōhō Shoten. Tōkyō Metropolis, 2022.

- Xiaoxuetang Database <https://xiaoxue.iis.sinica.edu.tw/>

CC BY-SA 4.0